Charak

As a festival and a ritual, Charak definitely goes back to pre-Hindu roots that were later absorbed into Hinduism. Its rituals of self-flagellation, inflicted torture and endurance through pain can be seen in different parts of India even now, especially, in the South. In Tamil country, for instance, the same rites of self-torture go under the name of Thaai-Poosam. Where the Rarh part of Western Bengal region is concerned, Charak has been celebrated as an essential part of worship of Dharma Thakur, the primordial god of the indigenous people, throughout the month of Baishakh, that is in April-May.

Over time, one of the main festivals celebrating Siva came to absorb the rites of Charak and be celebrated as Gaajan, in the last part of the preceding month, i.e., Chaitra. Both these months incidentally herald the hottest part of the year, and the ritual may have originated as rain invoking ceremony: to torture the self, to bring rains to parched dusty fields and cracked soil. It became institutionalised in the months of April-May, as the Gaajan of Siva or Dharma.

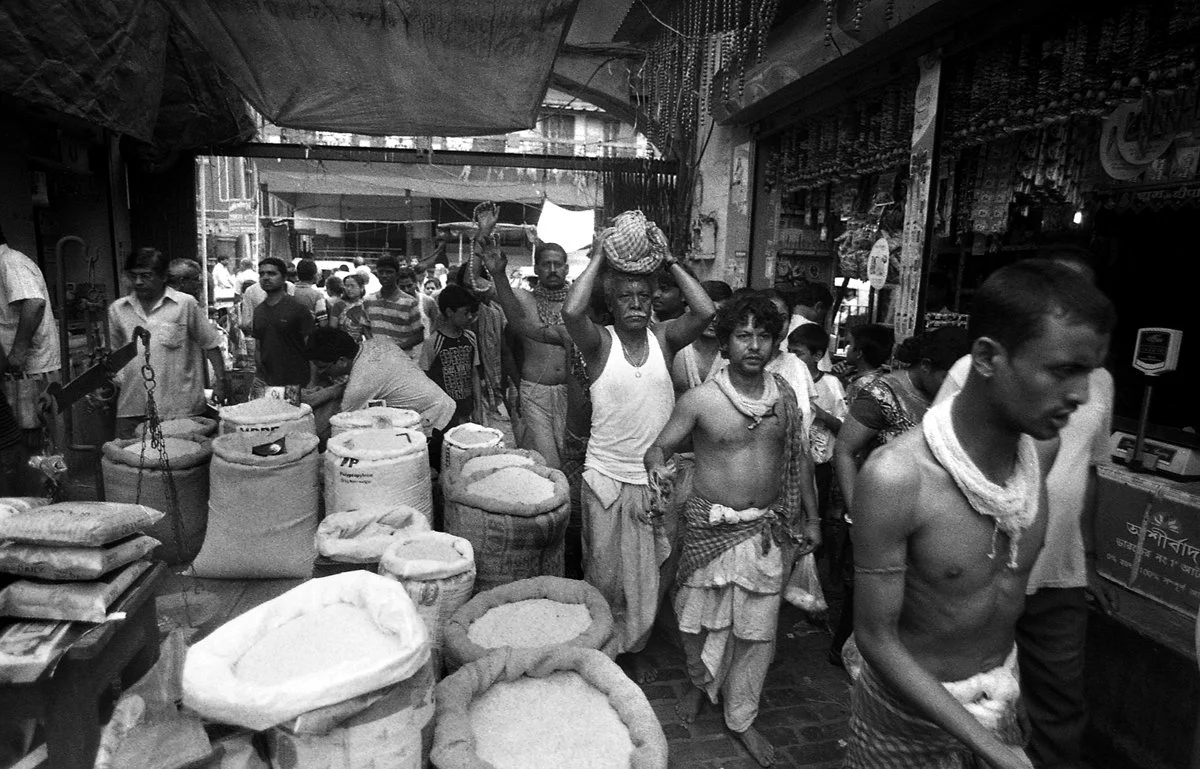

The central public attractions of both the ceremonies are the rites that inflict wounds and gashes. The ceremony of Charak is the most awesome spectacle, as hooks are inserted into the backs of devotees, who are then tied to ropes and are swung around in circles, high up in mid-air. The entire body just rests upon the hook and the swinging rope. Worshippers are primarily rural audiences, even today, but in the metros of Kolkata and Chennai, the practices can also be noticed in some pockets, during the month of April and May.

The British were alarmed at such horrendous practices, both in Bengal Presidency and in Madras. We have reports from the early 19th century, about Christian missionaries and English-educated citizens, as also various Committees, petitioning to the British about the barbarous practices of hook swinging at the Charak festival, as “cruel and degrading, without having any religious sanction”.

The Commissioner of Polices were ordered action as were the Superintendents of Police: but the ritual only receded in its intensity, it could not be stopped altogether. There is evidence of the continuing observance of Gaajan, along with Charak rites of self-torture, that amaze crowds. The celebration of Gaajan goes far beyond the hook-swinging of Charak and has several other components, like walking on burning coals with naked feet, rolling the body over several circles of thorns, jumping from heights onto open blades, and so on. Needles are also pierced through tongues and lips, as well as between the cheeks, and on the chest and back: usually without bleeding. It all depends on local practices. The central theme continues to be self-flagellation.

The only major departure that one sees in the modern period is that, in most places, the hook in the back is avoided, because of the law. The bodies of the devotees are strapped to the pole with long ropes, and swung around, nevertheless. As everyone knows, where the long arm of the law does not reach, the practice of piercing the back with hooks continues, both in Bengal and in Tamil Nadu.

One must remember that these rites of self-torture are not unique to popular Hinduism and that these practices are similar to the observances seen in Shia rituals of Maatam during Muharrum. It is also seen during Easter, in the Philippines or in Latin American countries. Folk devotees carry painfully-heavy ‘crosses’ on their back up the hill with crowns of thorn piercing their heads, in what is called the Passion of Christ. It is amazing how all formal religions have tried to “cleanse” these painful practices, but their devotees continue to observe them, nevertheless, to fulfill vows or as them as the ultimate expression of devotion to their deities.

- Text

Jawhar Sircar IAS (R) & MP ( Rajya Sabha )

...............